Two generations of the Marston-Phillipse family by English painter John Wollaston (1710-1775)

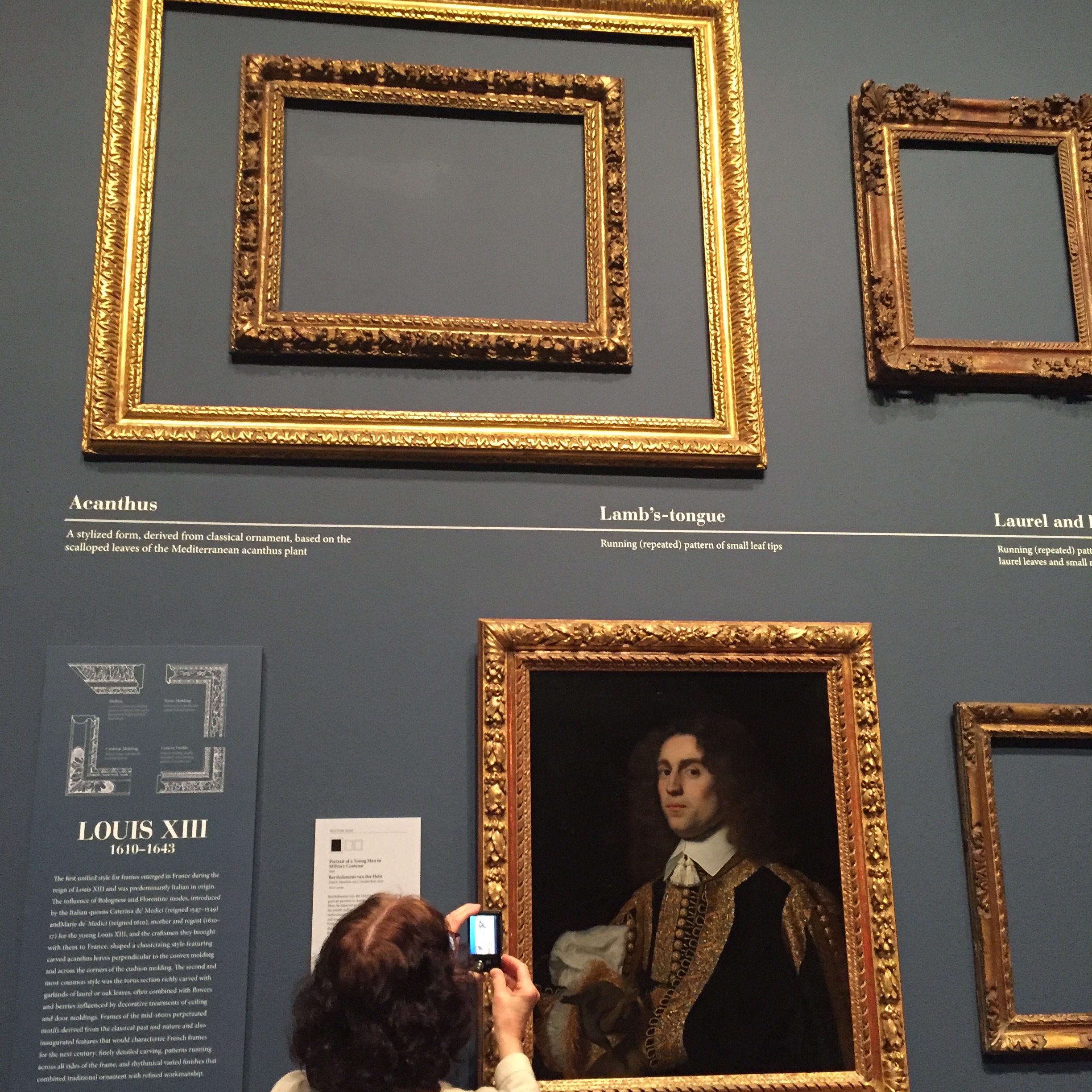

On view now at the Museum of the City of New York Picturing Prestige: New York Portraits, 1700-1860 draws from the permanent collection and showcases some of the finest examples of early New York City portraiture. Early, in this case, means the late 18th and early 19th centuries when New York became a thriving, populous center of the still-young United States. Portraits were the most popular form of painting at the time, an important and prestigious chronicle of the wealthy and successful merchant class.

From a frame perspective the exhibition offers the opportunity to see some fine examples of late 18th Century carved and gilded frames as well as some fine examples of American frames typical of the 1840’s. I recently walked through the exhibition with Dr. Bruce Weber, MCNY Curator of Painting and Sculpture and curator of the show; much of the information about the artists and sitters included here draws upon Bruce’s knowledge and research.

As you enter, there are two remarkable groups of late-18th Century portraits; at left is a group of four portraits depicting two generations of the Marston-Phillipse family by English painter John Wollaston (1710-1775).

At right are four portraits of mother Sara Bogart Ray (Mrs. Richard Ray) and her three sons by John Durand (active 1766-1782). Little is known of Durand though historical material regarding the portraits indicates that the frames were made by Thomas Strachan, a British maker working in New York.

Sara Bogart Ray (Mrs. Richard Ray) and her three sons (Cornelius Ray, Richard Ray, Jr., and Robert Ray with dog) by John Durand (active 1766-1782).

The frames on the Wollaston and Ray portraits are different in design though both are not only carved, but also typify the British Rococo style popular during this time. Both expressions are light and delicate in appearance and include C-scrolls, S-scrolls and gadrooning. The Wollaston frames have a leafy primary section with gadrooning as a small accent at the sight edge and pierced carving at the corners and centers.

Mary Crooke Marston (Mrs. Nathaniel Marston), c.1751 by John Wollaston (1710-1775)

Detail of one of the four frames on the portraits by John Wollaston

In contrast, the Ray frames eliminate the central panel entirely and use both the gadroon ornament as a bold anchoring motif at the sight edge

Richard Ray,Jr., c. 1766 by John Durand (Active 1766-1782), Detail

Detail showing gadroon sight-edge on Richard Ray, Jr. by John Durand

and exuberant yet delicate scrolls around the entire frame- with the exception of the corners and centers, which are accented by acanthus leaf flourishes.

Detail showing acanthus leaf flourishes and C-scrolls at centers on Richard Ray, Jr. by Durand

It is remarkable that all these delicate frames have survived intact!

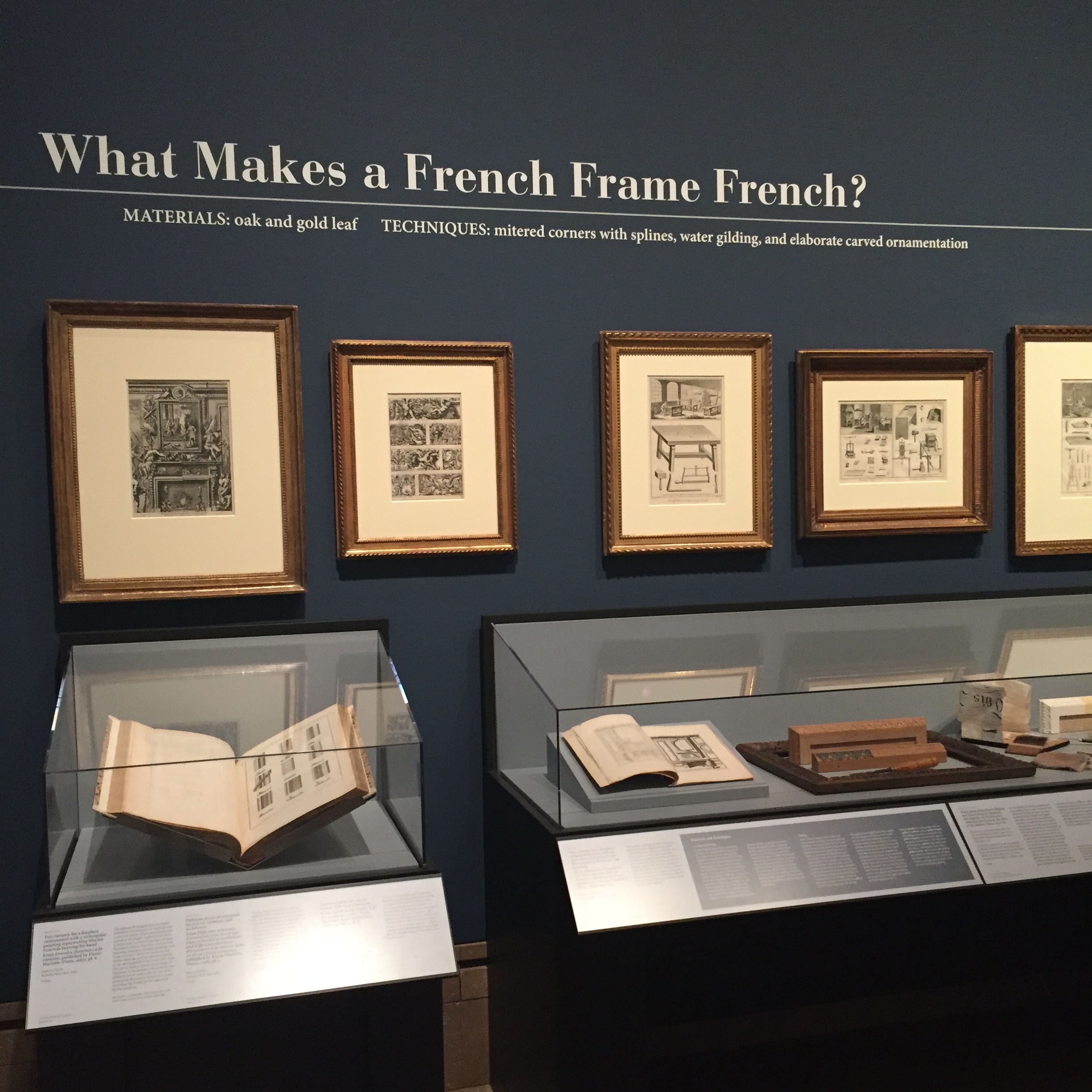

Also noteworthy in the show are a number of frames from the 1840’s. In America during that period it was popular to use a silk tulle on the frame as a ground for the applied ornament. The tulle gives the surface a delicate topography

Detail showing silk tulle ground on frame for Ann Eliza Moserman Brooks (Mrs. John E. Brooks), d.1845 by Shepard Alonzo Mount

not unlike that of the intricate surface recutting seen in earlier 18th Century French Louis frames.

Detail showing surface recutting on an 18th century French Louis XV carved frame.

Indeed, each of the frames on the portrait of Ann Eliza Moserman Brooks (Mrs. John E. Brooks), dated 1845 by Shepard Alonzo Mount (1804-1868) seen below

and the double portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Henry Augustus Carter, circa 1848 by Nicholas Biddle Kittel (1822-1894)

Mr. and Mrs. Charles Henry Augustus Carter, circa 1848 by Nicholas Biddle Kittel (1822-1894)

Detail of frame on Mr. and Mrs. Charles Henry Augustus Carter, circa 1848 by Nicholas Biddle Kittel (1822-1894)

both echo Louis XV frames with swept sides, projecting corners and centers and lush floral embellishments. Typical of the ornamentation of 19th Century frames, all these motifs were molded and applied not intricately carved as were their 17th and 18th-century French predecessors.

Late 18th Century French Louis XV style carved frame

These late 18th Century and 1840's frames are just highlights- there are a number of other excellent frames in the Museum of the City of New York exhibition- on view until September 18, 2016, it is well worth a visit.