Originally published in Notes from a Visiting Scholar, Fall 2020, Menconi+Schoelkopf

American modernist John Marin (1870-1953) explored the role of frames and his artwork extensively throughout his career. Marin both incorporated them figuratively within his compositions and utilized them literally to enhance and enclose his artworks. Marin was educated in engineering and practiced as an architect throughout the 1890’s, a perspective that surely informed his artistic practice and frame choices. Early simple frames that surround many of his early watercolors were finished in nuanced shades of white and others were gilded in tones of silver. Later in his career, from the 1930’s onward, Marin created surprising, unusual frames, some modest wood profiles that he painted with patterns and colors related to the artwork and others that included driftwood and other found materials. These later frames by themselves may seem humble and unsophisticated, yet when united with Marin’s artworks, they add dramatic and compelling visual interest.

We are fortunate to know a great deal about Marin’s framing practices. Two publications in particular devote valuable attention to Marin’s frames. The first is Ruth E. Fine’s book John Marin of 1990. In addition to her discussion of Marin’s frames [1], many of Marin’s artworks are illustrated in color in their original frames throughout the book. The second book John Marin’s Watercolors: A Medium for Modernism includes a chapter that details the thorough investigation and analysis of the framing treatments on seventeen Marin watercolors and two oils spanning the years 1914-1947; retaining their original framing treatments [2], most had been gifted to the museum in 1949 by Georgia O’Keeffe as the executrix of the Estate of Alfred Stieglitz.

Marin’s early frames were made by George F. Of a frame shop founded by George F. Of, Sr. [3]. George F. Of, Jr. (1876-1954), an artist in his own right, worked in his father’s shop as a boy and took over the business upon the death of his father in 1905 [4]. Alfred Stieglitz had been working with George F. Of at least by 1902 - the inaugural issue of Camera Work from January 1903 contains a banner ad for George F. Of that lists the address 3 East 28th Street; in the same issue under ‘Some News Things Worth Looking Into’ it notes “The new store of Geo. F. Of, whose framing of photographs has added to the admiration expressed for many of the American prints.” It was from the 28th Street address that in 1915 Of relocated to 274 Madison Avenue (between 39th & 40th Streets), much closer to Stieglitz’s Gallery 291 located at Madison Avenue between 40th and 41st Streets.

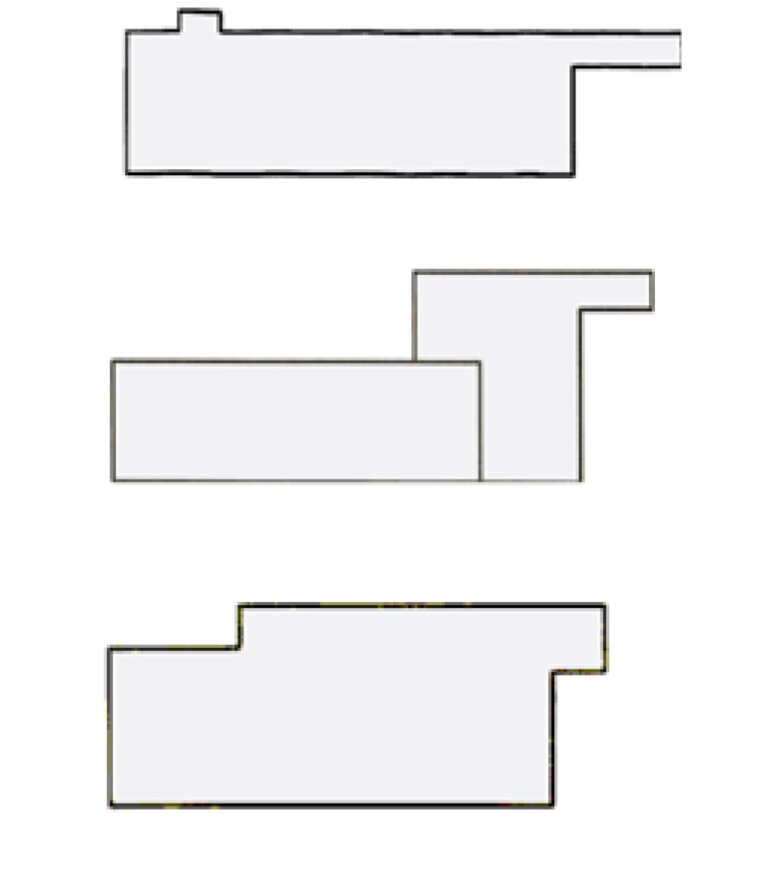

Fig 1 Step frame profiles. Courtesy Menconi + Schoelkopf

Fig 2 Replicating the George Of white frames of the period, translucent washes of blue, green, and gray have been applied to this reproduction white frame on Little Fir Tree, Deer Isle, 1921. Courtesy Menconi + Schoelkopf

Among several profiles that Marin favored in the 1910’s were several iterations of ‘step’ frames. (Fig 1) Often finished in silver leaf, these are frequently seen on Marin watercolors and paintings. Interestingly, in addition to the more well-known silver-gilded frames, there are a number of other original Of frames that are finished in white. Not just any white- as detailed in the Chicago book, Of utilized a variety of surface treatments where white enamel paint has been modified by the use of specific colors underneath and also translucent washes of blue, green and gray on the outside (sometimes added by Marin himself) that speak directly to the colors in each individual watercolor. (Fig 2)

An invoice [5] from Of to Stieglitz shown in the Chicago book for the ‘Marin account’ enumerates many different frames ordered with drawings of their profiles and notes regarding their finishes that include both silver leaf and ‘cool white enamel’. The framemaker’s invoice is on letterhead listing the address ‘274 Madison Avenue’ but this has been marked out and a stamp at left shows the shop has relocated to 126 West 57th Street. This tells us that the invoice is from July 1926 or later when city records list Of at the new address. These addresses and their corresponding dates illuminate how long Marin chose to use certain frame profiles and finishes.

Working with Menconi + Schoelkopf to effectively frame a number of Marin artworks has offered fascinating opportunities. Marin’s Weehawken Series, executed 1910-1916, and comprised of about 100 oil paintings all in small formats (12” X 8”, 14” X 10”, etc.) range from abstraction to figuration and employ dazzling color and brushwork. When asked to propose a frame for a significant group of the series I immediately thought of the range of ‘step frames’ that Marin and other artists used during these years and beyond. This approach honors Marin’s early frame choices and stylistically situates them in the early teens when they were painted.

Fig 3 Detail of a silver leaf Weehawken Sequence frame. Courtesy Menconi + Schoelkopf

Fig 4 A framed Weehawken Sequence painting. Courtesy Menconi + Schoelkopf

After considering several iterations we settled on a step profile 3” wide, with the primary wide flat closest to the opening of the frame. (Fig 3) The nuance of any surface, whether painted or gilded, is critical to a successful frame treatment and this is especially true when framing art of the early 20th Century. We settled on silver leaf that was then toned with a translucent colored wash that complemented the paintings. The result was just right. (Fig 4)

Fig 5 Before and after reframing of Street Movement, Nassau Street, No. 1. Courtesy Menconi + Schoelkopf

Fig 6 Light silver leaf finish and silver finish with a carefully toned wash. Courtesy Menconi + Schoelkopf

Another example illustrating the importance of the finish was the reframing of Street Movement, Nassau Street, No. 1 of 1936. The drawing/watercolor had been framed in a reproduction of an early Marin profile but was finished in a warm yellow gilding with no mat. Both the warm tones of the gold and the compressed border around the image constrained the overall effect. Instead, a narrow mat, in a color more congruent with the color of paper that grounds the image, was added and a less-wide style of step frame was chosen that employs one wide, recessed frieze - a simple profile that provides the perfect foil to the dynamic energy of Marin’s drawing of downtown New York City. (Fig 5) In this case, although still using silver leaf, the finish was carefully toned with a wash that gave the surface a darker, pewter shade that is supportive of the darker tones in the composition and still retains the elegant luster of a gilded surface. (Fig 6)

Marin’s later frames are remarkable for their inventiveness and originality. Marin made use of several different profiles for his later frames. Some were simple, others more complex. Some with painted surfaces to match the compositions and others chip-carved and embellished with shapes and lines that reinforced the same features in his artworks. In his eighties Marin remarked “If I were younger, I’d plunge into sculpture, but my frame-making will have to satisfy my sculptural urges” [6].

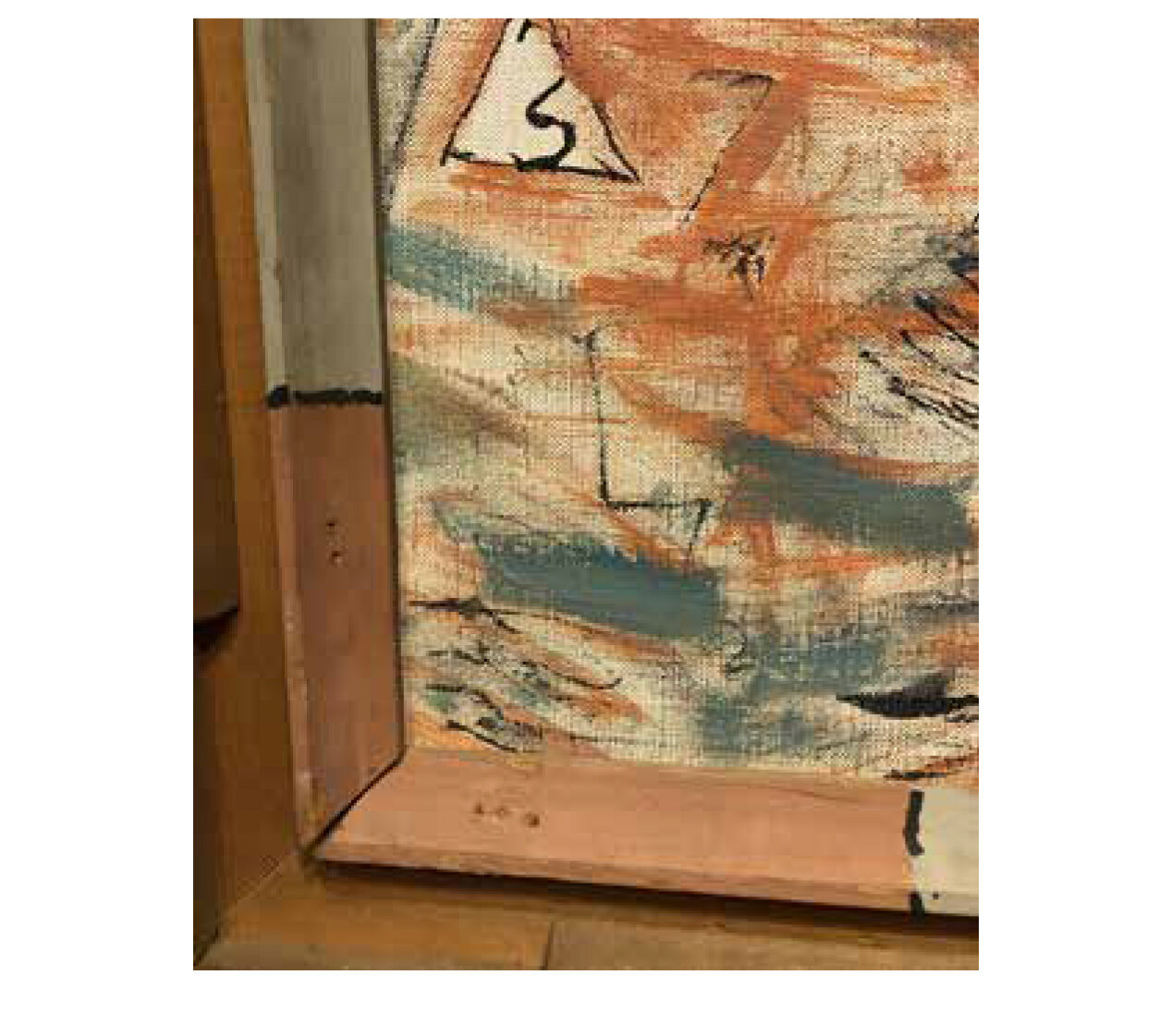

One such example is the frame original to Movement in Red and Grey No. 1 of 1949. (Fig 7) By leaving most of the wood surface in its natural state the warm tones speak directly to the colors in the composition. Further grounding the artwork within its surround Marin has painted all four inner sections of the frame with a central passage of the same pale grey in the composition and asserted the edges with a black calligraphic line that echoes those within. (Fig 8)

Fig 7 Movement in Red and Grey No. 1 in its original frame from 1949. Courtesy Menconi + Schoelkopf

Fig 8 Detail of original frame showing pale gray and black calligraphic lines. Courtesy Menconi + Schoelkopf

While striking in their effect and clearly a component of the artist’s aesthetic vision many of the frames made by Marin were removed from his artworks over previous decades. As early as 1963 framer Henry Heydenryk remarked on the practice of artists painting their frames and noted that Marin had done so “…so forcefully and assiduously that the coloring and patterns on the frame became too dominant for the painting in it. Many owners have replaced his frames with more restrained, more neutral moldings” [7].

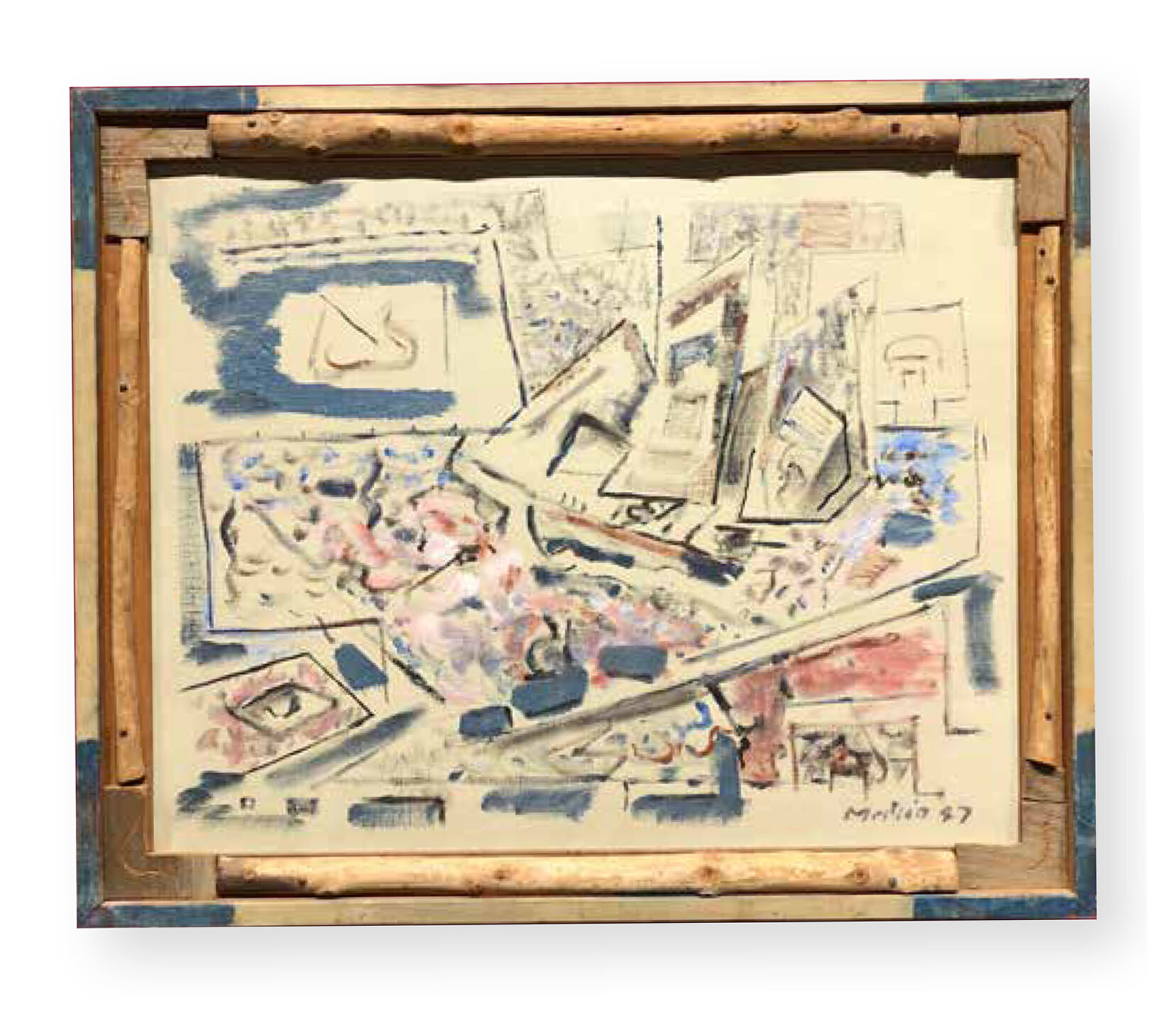

Fig 9 Movement: Sea Played with Boat Motive, 1947, in one of Marin’s original driftwood frames. Courtesy Menconi + Schoelkopf

Happily, some of these frames have survived and were acquired by Menconi+Schoelkopf so that they could be repatriated with Marin artworks. One such example is the marriage of Movement: Sea Played with Boat Motive, 1947 with one of Marin’s ‘driftwood’ frames. (Fig 9) The frame is narrow and anchored by corners painted in blue; narrow lengths of driftwood are affixed to each frame section with unapologetically visible screws. Each inner corner contains an ‘L’ shaped bit of coarse wood that is scored with a undulant line much like those on the canvas. Though not original to this particular artwork the match is not only successful but revelatory-a telling example of the transformation affected by the use of the artist-made frame.

Marin artworks embraced by Marin frames become something more, calling to mind the 1937 observation by critic Ralph Flint, “He has done a neat trick in framing…in an arrangement of weathered strips picked off the beach in Cape Split…a frame that will have its place in present-day Americana as sure as collectors are collectors” [8].

NOTES

1. Fine, Ruth E., John Marin, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Abbeville Press Publishers, New York, 1990. 201–207

2. Tedeschi, Martha and Kristi Daum et. al., John Marin’s Watercolors: A Medium for Modernism, The Art Institute of Chicago, Yale University Press, 2010. 58–77

3. George Ferdinand Of, Sr. (unknown birthdate-d.1905) immigrated to the US from Germany in 1867 and founded the shop in New York in 1873.

4. Of Jr. studied at the Art Students League for five years beginning in 1893 and spent a year with Abbott Thayer on his Dublin, NH farm in 1900. Later that year Of, Jr. accompanied the Thayer family to Italy and visited relatives in Germany, studied briefly in Munich and Paris and returned to courses at the League. Of, Jr.’s paintings were championed by many including Walter Pach though it seems that the demands of running a successful frame shop limited his career as a painter.

5. Alfred Stieglitz/Georgia O’Keeffe Archive, Yale Collection of American Literature Bienecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New Haven Connecticut.

6. Gertrude Benson, “82 Year Old Man Tells Artist’s Credo,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 6, 1952.

7. The Art and History of Frames, Henry Heydenryk, James H. Heineman, Inc. 1963, pg 98.

8. Ralph Flint “John Marin Blazes New Trails,” The New York Sun, 6–16, 1937.