Suzanne Smeaton, independent picture frame historian, considers the frames of one of the Ashcan painters in the light of the recent exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington (June to October 2012), the Metropolitan Museum, New York (November 2012 to February 2013) and at the Royal Academy, London (March to June 2013).

Researching frame choices of the Ashcan painters for an essay in the exhibition catalog of 2007 for Life’s Pleasures: The Ashcan Artists’ Brush With Leisure, 1895-1925 organized by Jim Tottis at the Detroit Institute of Arts, was an early opportunity to explore Bellows’ frame choices. Of the frames known to be original to Bellows’ paintings[2], all utilize simple yet sophisticated profiles, are devoid of ornamentation, and all are gilded. The three frame profiles discussed here will be referred to as ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’ in the interest of clarity. In that essay for Life’s Pleasures… the frame style referred to as a ‘Bellows frame’ (the ‘A’ profile) was discussed [3].

‘A’ profile, courtesy of Eli Wilner & Company, Inc.

‘A’ profile, courtesy of Eli Wilner & Company, Inc.

In that research we were able to attribute the frame to the New York framemaker M. Grieve Company, as many of the frames of this style bear his stamp on verso.

Stamp of M. Grieve Company, courtesy of Eli Wilner & Company, Inc.

Maurice Grieve, photographed by Peter A. Juley & Son

Known as ‘the master of roses’ due to his skill in woodcarving, Grieve came from a long line of woodcarvers [4]. The Grieve Company is known to have worked with the illustrious art dealer Joseph Duveen and through that association made many frames, among them the frame for The Blue Boy by Thomas Gainsborough, which belonged to Henry Huntington [5].

George Bellows, Stag at Sharkey’s, 1909, o/c, 92.0 x 122.6 cm, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Hinman B. Hurlbut Collection, 1133.1922

The ‘A’ profile, as in the frame of Stag at Sharkey’s, can be seen as a modern-day interpretation of a reeded moulding: in this case the repeating parallel lines are carved in undulant uneven strokes that are more exaggerated in size than traditional reeded mouldings. The progression of parallel passages also vary in width and incorporate a soft curve as the frame slopes from its highest point at the outermost top rail down toward the sight edge and display the pleasing irregularities of a hand-carved frame. The sumptuous, inflated characteristics of the frame provide a sympathetic enclosure for Bellows’s lush brushwork.

George Bellows, Stag at Sharkey’s, The Cleveland Museum of Art, detail of frame.

Interestingly, the frame appears on Bellows’s boxing paintings dating from as early as 1907 (Club Night, National Gallery of Art, Washington), and Stag at Sharkey’s of 1910 (Cleveland Museum of Art), to as late as 1924 (Dempsey and Firpo, Whitney Museum of Art; Mr. and Mrs. Phillip Wase, Smithsonian American Art Museum). The ‘A’ profile also appears on Polo at Lakewood of 1910 and Snow Dumpers of 1911 (both Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio) although the frame surfaces have been whitewashed and much of the original gilding is obscured.

George Bellows, 1910, Polo at Lakewood, Columbus Museum of Art

George Bellows, 1910, Polo at Lakewood, Columbus Museum of Art, detail of frame.

It is questionable that this is an original surface treatment as there are no other frames on Bellows’ artworks in this profile or any others that bear the finish.

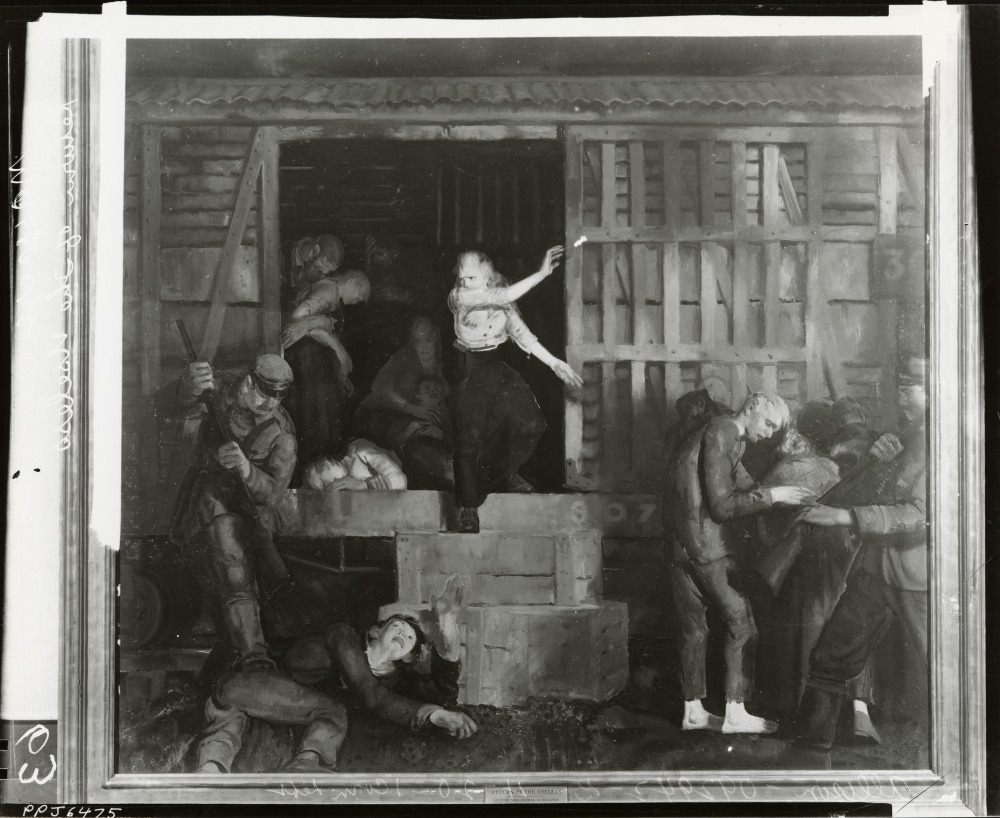

George Bellows, The Return of the Useless, 1918, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville

Nearly all of the War Series paintings of 1918 are also framed in the ‘A’ profile by Grieve. An interesting exception is The Return of the Useless: the original frame is captured clearly in a photo from the Peter A. Juley & Son collection of archival photographs [6] in a cassetta variant.

Two paintings are exhibited in two different versions of traditional reeded mouldings that appear to be original; they are Summer Night, Riverside Drive of 1909 (Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio; New York venue only) and Cliff Dwellers of 1913 (Los Angeles County Museum of Art).

Robert Henri, Dorita, 1923, LeClair Family Collection

Robert Henri, Dorita, 1923, LeClair Family Collection, detail of frame

While the ‘A’ profile frame is still most frequently associated with Bellows, the frame also surrounds a number of paintings by Bellows’s mentor Robert Henri. Those include Viv Reclining (Nude) (1916, LeClair Family Collection), Portrait of Marcia Anne M. Tucker (1926, Private Collection), and Dorita [7]. Who first started working with Grieve? Was it Henri or Milch? An interesting question yet to be answered.

Period photographs of artworks, exhibition installations and other contemporary settings prove to be an invaluable resource in learning about framing choices and practices: for example, mages of the George W. Bellows Memorial Exhibition held by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, from 12 October 12 1925 to 22 November 1925:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The practice of masking out the frame from an artwork in documentary photographs and often little or no documentation regarding the frames on artworks by institutions and individuals makes it difficult to trace the history of framing practices. The plight of the frame historian is further exacerbated by the fact that exhibitions such as the current one, drawn from many collections both public and private, strictly prohibit photography across the board in deference to privacy and copyright issues. How unfortunate when detail photos of a frame could be allowed without the artwork included. Alas, this is not the case and many frames in the show cannot be illustrated here for this reason[8].

‘B’ profile, courtesy of Eli Wilner & Company, Inc.

George Bellows, 42 Kids, 1907, o/c, 42 x 60 1/4 ins, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington DC, Museum purchase, William A. Clark Fund 31.12

George Bellows, 42 Kids, 1907, detail of frame

The next profile, here referred to as the ‘B’ moulding, is by a maker yet to be identified. The moulding appears on 42 Kids of 1907 (Corcoran Gallery of Art), The White Horse of 1922 (Worcester Museum of Art), Fisherman’s Family of 1923 (Private Collection), and Lady Jean of 1924 (Yale University Art Gallery; shown in Washington only). It is, at first glance, a simple moulding but it has a prominent round near the sight edge that curves back toward the outer edge of the frame forming a pronounced hollow that sets it apart from a more standard expression.

George Bellows, Lady Jean, 1924, Yale University Art Gallery

Much like the ‘A’ profile, the ‘B’ profile eschews decorative embellishments in favor of an understated yet studied profile. In Lady Jean the frame is accented with a black painted band in the hollow.

Lady Jean, Yale University Art Gallery, detail 1 of frame

Lady Jean, Yale University Art Gallery, detail 2 of frame

Not having seen the use of black paint as an accent on any other Bellows’ frames, I questioned whether the black was original. Happily, a photograph from the Juley archive documents that this accent certainly is original.

It is worth noting that two paintings do appear in conventional ‘Salvator Rosa’ profiles [9], Emma in the Black Print of 1919 and Emma and Her Children of 1923 (both MFA Boston).

The third and final profile discussed here is also by a known maker, Albert Milch. Albert Milch (1881-1951) was the younger brother of Edward Milch (1865-1953). Both Austrian-immigrant brothers worked independently[10] before going into business together in 1916 to form E. & A. Milch, a gallery specializing in American Art.

‘C’ profile, courtesy of Eli Wilner & Company, Inc.

The ‘C’ profile is a cassetta variant. Where the two cassetta frames on Paddy Flanagan (1908, Wolf) and Return of the Useless (1918, CBMAA) are more conventional designs, the ‘C’ profile is a third more overtly hand-wrought frame with carving on the frieze in a shallow irregular pattern that recalls light playing on the surface of water.

George Bellows, Arcady, 1913, Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio

Bellows, Arcady, detail of frame

Bellows’ Arcady of 1913 (not in exhibition) appears in this frame and it is a fitting complement to the composition with the mountainous foreground and the sun-lit sea beyond [11].

Stamp of Albert Milch, 78 West 55 Street, NY, courtesy of Eli Wilner & Company, Inc.

It is the stamp of Albert Milch at 78 West 55th Street that is on the verso of profile ‘C’, telling us that the frame was made c. 1911-1913. City Directories indicate that Albert Milch moved to 78 West in 1911 and stayed until 1913.

Label of E. & A. Milch, Inc., 108 West 57 Street, NYC, courtesy of Eli Wilner & Company, Inc.

This was well before the Milch brothers went into business together in 1916 and before either of Bellows’ exhibitions at E. & A.Milch in 1917 and 1918[12]. Was Bellows framing paintings first with Grieve and then with Milch? What caused him to change frame makers? Or did he use both frame makers simultaneously? We note the same pattern with Henri who used the Grieve ‘A’ moulding and also later framed many paintings with Milch.

Beyond illuminating what Bellows’ frame choices were during his career, the Bellows exhibition and the variety of frame styles on view provoke tantalizing questions about the aesthetics and commerce of framing during this expansive and dynamic period in modern American Art. Further investigation will surely provide us with even more insights into the frames on George Bellows paintings.

[1] Brock, Charles et al. George Bellows, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 2012.

[2] Email correspondence between the author and H. Barbara Weinberg, Alice Pratt Brown Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture, Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 28, 2012. “Charlie Brock believes that the following paintings in the exhibition are in original “Bellows” frames, most of which are modest and fairly uniform:

Paddy Flanagan

Cliff Dwellers

Forty-two Kids

Polo at Lakewood

Snow Dumpers

Return of the Useless

Dempsey and Firpo

Fisherman’s Family

Emma and Her Children

The White Horse

Charlie bases his opinion on 1907 views of Bellows’ studio and 1925 views of the Met’s Memorial Exhibition.”

[3] Smeaton, Suzanne, ‘Embracing Realism: Frames of the Ashcan Painters, 1895-1925’, in Life’s Pleasures: The Ashcan Artists’ Brush With Leisure, 1895-1925, London/New York/ Detroit Institute of Arts with Merrell Publishers Limited, 2007. pp. 90-105.

[4] New York Times, February 18, 1955, p. 23 (Maurice Grieve obituary.) This article gives further information on the firm of M. Grieve.

[5] For further information on Duveen’s business in frames see: Penney, Nicholas, ‘Duveen’s French Frames for British Pictures’, The Burlington Magazine, June 2009, p. 388-394.

[6] The Peter A. Juley & Son Collection holds 127,000 photographic black-and-white negatives documenting the work of 11,000 American artists. Peter A. Juley & Son, one of the largest and most respected fine-arts photography firms in New York, served artists, galleries, museums, schools, and private collectors from 1896 to 1975. The collection, acquired by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 1975, constitutes a unique photographic record of thousands of works of American art, sometimes providing the only visual documentation of a changed, damaged, or lost original. The Juley Collection also contains 3,500 portraits of artists, including formal poses as well as candid shots that depict artists working in their studios, teaching classes, and serving as jurors for exhibitions.

It is possible to search the entire Juley Collection Catalog online via SIRIS (Smithsonian Institution Research Information System). Use the Limit feature to view works only from the Juley collection. The collection is being digitized with over 10,000 images already online. You can also view a selection of Juley photographs on Flickr Commons. For more information, email sapa[at]si.edu.

[7] Smeaton, 2007, p. 102

[8] For a cogent discussion of this topic see ‘Why Can’t We Take Pictures In Museums?’ by Carolina A. Miranda, Art News, 13 May 2013

[9] Mitchell, Paul and Roberts, Lynn, Frameworks: Form, Function & Ornament in European Portrait Frames, London: Paul Mitchell in association with Merrell Holberton, 1996, p. 30

[10] New York City Directories 1896-1946. Edward Milch is listed as early as 1894 as ‘Gilder’ at 118 E. 119th Street. Albert Milch’s first listing is ‘Frames’ at 122 W, 45th Street.

[11] Another period frame in this same profile and finish and bearing the Albert Milch stamp from 78 West 55th Street was also in the inventory of Eli Wilner & Company. The frame was marked in pencil on verso: ‘Bellows Pigs and Donkeys’. The painting is now in the collection of the Art Gallery of Hamilton, Canada.

[12] Eli Wilner & Company has also had a frame in their inventory with a foil label for Albert Milch: ‘ALBERT MILCH, MANUFACTURER, HIGH GRADE PICTURE FRAMES 101 West 57th Street, New York City’. City directories indicate that this address dates to 1916.