This past October 2017 I had the pleasure of presenting a Members-Only lecture for the Barnes Foundation.

The presentation focused on Dr. Albert Barnes’ framing choices, how he made those selections, who provided them and the three American artist-framemakers he patronized.

View of an ensemble at the Barnes Foundation

The archives at the Barnes Foundation is a treasure trove of information and includes Dr. Barnes’ extensive correspondence. (Happily the doctor’s letters were all typewritten.) That said, it was also a delight to see handwritten letters and even a frame-centric letterhead belonging to Robert Laurent.

Letterhead on an invoice for frames from Robert Laurent to Dr. Alfred Barnes

In his early years of collecting Barnes worked extensively with noted French dealer Paul August Durand-Ruel so much so that in 1915 Barnes wrote to Durand-Ruel “…my collection is practically an annex of your business.” There is frequent discussion of the frames on the artworks Barnes was purchasing from Durand-Ruel that make it clear Barnes was attuned to the impact of frames. On April 12, 1912 Barnes wrote “I hope you will agree with me that paintings such as I have bought from you should be furnished in frames that are worthy of the paintings, and fitting to be hung in the surroundings that they would find in my residence. If the frames which you have are old, dilapidated and inappropriate, I would prefer not to receive them, and believe that I am not asking too much of you to see that I am provided with suitable frames for the paintings in question.” And two days later on April 13, 1912, “The reason I write you about these frames is that a number of other paintings…obtained from various dealers in Paris, were provided with frames which would be a disgrace to even mediocre paintings. I have been compelled to discard these frames, and order new ones in keeping with the character of the paintings and setting in my residence where they are to be placed.”

Invoices and receipts in the archive show that Barnes purchased both (more costly) period frames in a variety of French ‘Louis’ frame styles. It is interesting to note that in France by the mid 19th century there was a revival of interest in the18th Century and artists such as Fragonard, Watteau and Boucher (including the Louis-style frames used on them) and it was followed by a renewed interest, by the 1880’s and 90’s, in the applied and decorative arts of the same period. Hence, 18th Century Louis style frames were seen on French Impressionist artworks; this retrograde approach was especially popular among American industrialists with their newfound fortunes: all things European were seen as a reflection of their Cosmopolitanism. (The prevalence of such frames on 19th and early 20th Century artworks is a topic unto itself.)

View of French Impressionist paintings in the Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art showing the taste for earlier French ‘Louis style’ frames.

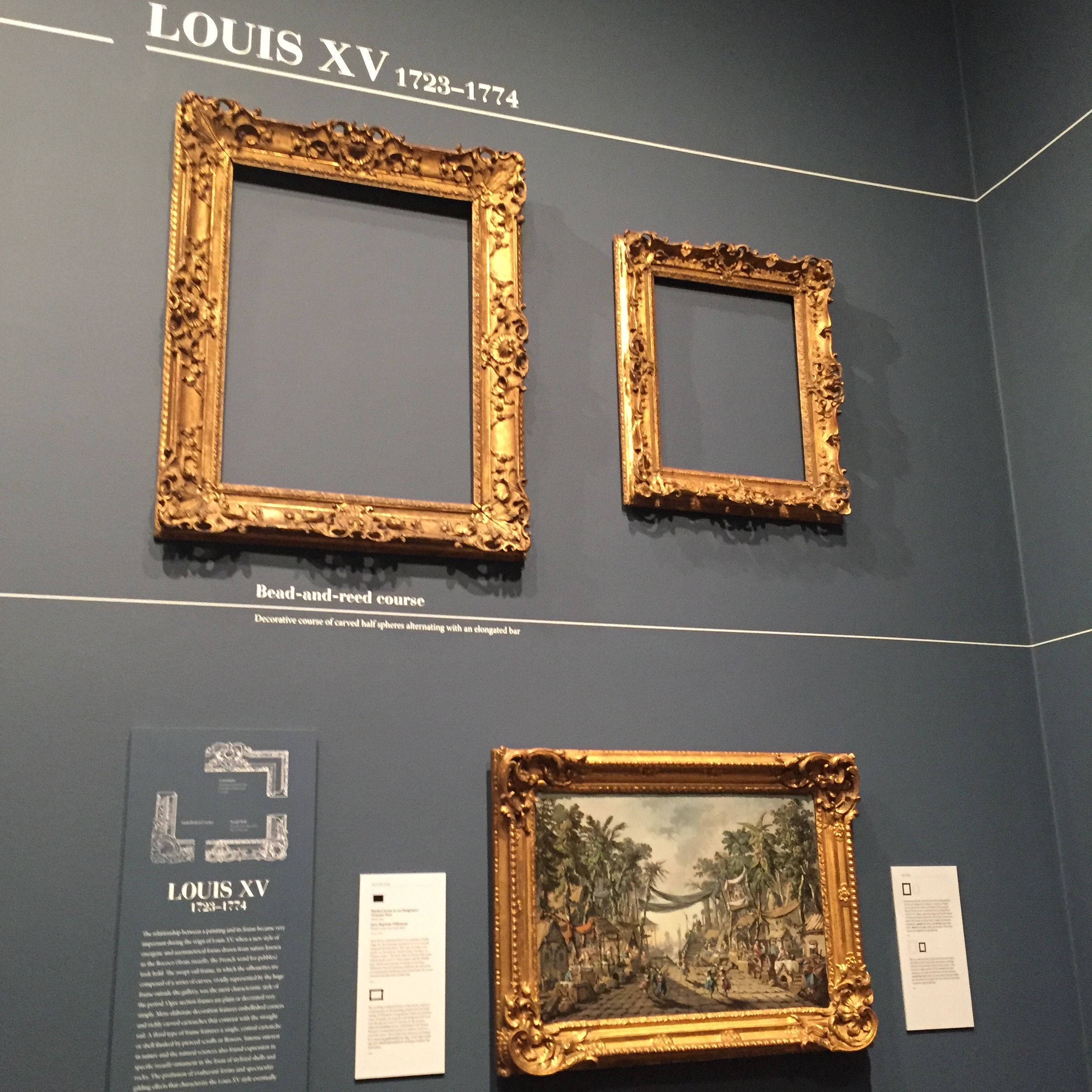

French Louis frames range in the extent of their ornamentation to include curvaceous Louis XV designs

as well as the more restrained, Neoclassical Louis XVI style.

View of restrained, classically-derived Louis XVI frames at the exhibition ‘Louis Style: French Frames, 1610-1792’ at the J. Paul Getty Museum (September 15, 2015- January 3, 2016)

A version of the latter was a molding so frequently utilized by Durand-Ruel that it became known as the ‘Durand-Ruel frame’. Referred to as a baguette frame, they are derived from Louis XVI French drawing frames. The moldings are a flat profile with a leaf tip or bead near the sight edge and a ribbon-and-stick pattern at the back edge.

Detail view of Durand-Ruel ‘baguette’ frames in the Louis XVI style in the exhibition ‘Pictures by Boudin, Cezanne, Degas, Manet, Monet, Morisot, Pissarro, Renoir, Sisley. Exhibited by Messrs. Durand-Ruel and Sons of Paris’ at Grafton Gallery, London, January & February, 1905.

9420 typical Durand-Ruel ‘baguette frame’ in the Louis XVI style.

Other variants employ a leaf tip at the back edge.

Detail image showing two variants of a French Louis XVI-derived baguette style frame

In the Autumn 1977 issue of The Barnes Foundation Journal of the Art Department (Volume VIII, No. 2) Violette DeMazia wrote a lengthy article ‘What’s In A Frame’ that discussed the aesthetics of frame choices in detail; in it she wrote: “more and more as time went on he inclined towards the simplicity of the Louis XVI as best serving to set off the artist’s statement. There were, of course, other considerations as well that governed his selection of frames…balance on the wall with paintings already there, for one; the introduction of variety within that balance for another; the color of gold, the tone of the patina, etc. not to mention the aesthetic character of the carving, the proportions and such of the frame itself.” Indeed, many artworks hang in this restrained style.

Ensemble showing the prevalence of the Durand-Ruel style frame.

Barnes installed his growing collection in ‘Ensembles’ and this certainly influenced his frame choices. In the same article noted above DeMazia offers insight into Barnes’ ongoing and ever-changing process of installation that illuminates why today we see that a number of frames including those by artist-framemaker Charles Prendergast have been cut and rejoined to sizes other than the original with little or no attention to the integrity of the original incised corner ornament.

Maurice Prendergast in a Charles Prendergast frame with incised sausage motif at corners.

Detail showing another frame where the sausage motif is truncated due to cutting and rejoining.

She explained: “…frequently Dr. Barnes would follow up the shipment…of the paintings he had purchased with a detailed list not only of where the paintings would be hung and where those that were thereby replaced should be rehung and so on, but also as a result of the new placements, which frames should now go on which paintings. It is not an exaggeration to say that an average of 50 moves might have to be made following the arrival of just one new painting. “ (Emphasis mine.)

Barnes’ attunement to the subtleties possible in a gilded surface are in evidence throughout his correspondence with artist-framemakers Charles Prendergast and Max Kuehne.

In a letter of April 15, 1915 he wrote to Prendergast regarding a shipment of 9 frames: “The color on two or three of them is rather glaring, of natural gold color, and need toning to slightly darker hue. I wonder if you would send a bottle of color to me by express with instructions how to apply it.” While adjusting the tone may have seemed a simple matter to Barnes any experienced gilder will surely counter this naïve viewpoint. In truth, the final toning of a gilded surface can be one of the most challenging and nuanced steps whether gilding new surfaces or matching one that is being restored. It is not surprising that Prendergast replied “I am afraid to have you touch those frames. You could spoil them very easy…”

While ordering frames from Max Kuehne,

Max Kuehne frame on work by Chaim Soutine

Barnes frequently admonished him to emulate the frames of Charles Prendergast in both form and finish. Perhaps Barnes did not understand that carving is much like handwriting and the work of each artisan has its own distinctive qualities. On Feb 2, 1921 Barnes wrote to Kuehne,

“I think it would be one of the best possible things you could do, to have the Prendergast frame around, because the tones are unique and there are certain features in the carving that differ materially from yours- and it seems that these two points that make the appeal between his frames and yours. I see no reason why, after a break with your old habits in regard to carving and finishing, you should not make a frame at least as good as Prendergast.”

Nonetheless, Barnes did appreciate Kuehne’s work and wrote to say so on June 2, 1921. “I am sorry I didn’t enthuse over the Matisse design frame but I assure you it is about the best I ever had from you and I’ll probably want more made later if I get other pictures.”

In conclusion, the thought and care Dr. Barnes lavished on the framing and presentation of his art collection should come as no surprise. From the detailed correspondence with his art dealers regarding not just the artworks but also their frames, to the avid patronage of American artist-framemakers, to his deliberative, complex and ever-changing Ensembles, Alfred Barnes’ singular vision served to create a collection unparalleled then or since and offers us nearly endless avenues to a deeper understanding of both the art he collected and the subtle yet profound effects of a painting thoughtfully framed.