Vigée Le Brun: Woman Artist in Revolutionary France, an exhibition: first shown at the Grand Palais, Paris, from Sept. 2015- January 2016; then at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, until 15 May 2016; and continuing at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 10 June- 11 September 2016; reviewed here by Suzanne Smeaton, independent frame historian.

It is always a gift when a new exhibition includes notable frames, and the show of portraits by Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is certainly one of these. This exhibition, which was called a ‘ravishing, overdue survey’ by the art critic of the New York Times, is indeed beautiful, displaying a comprehensive collection of the artist’s intimate, insightful and skillfully-wrought portraits. They range from work produced at the end of the 18th century in France, to those she painted in Italy, Austria and Russia, having been forced to leave her country at the outbreak of the Revolution. Marie Antoinette was an early advocate for and patron of Vigée Le Brun, and her patronage provided access to many in the upper echelon of French society, and later in the courts of Europe.

Having recently seen the exhibition Louis Style: French Frames, 1610-1792 at the Getty, I was struck by the array of fine French frames, especially the many Louis XVI examples. I was also fortunate to walk through the exhibition with my friend and colleague Cynthia Moyer, Associate Conservator for frames in the Paintings Conservation Department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In addition the fact that she has worked on some of the frames in the show, Cynthia’s keen eye, and specific knowledge of gilding, French decorative art and frames, provided me with a deeper understanding of the nuances of many of the patterns there.

Jacques-François Le Sèvre, c.1774, private collection; Etienne Vigée, post 1773, Saint Louis Art Museum; Mme J-F Le Sèvre, c.1774-78, Private Collection

Near the entrance of the exhibition is a telling installation of three portraits showing Vigée Le Brun’s stepfather, brother, and mother, each framed in a different style, which together encapsulate contemporary taste.

Louise Vigée Le Brun, Madame Jacques-François Le Sèvre, c.1774-78, 25 5/8 × 21 1/4ins (65 × 54 cm), Private Collection

The oval portrait of the artist’s mother, Mme Le Sèvre (1774-78), is a quintessential late 18th century NeoClassical design, with a flat top edge, leafy acanthus in the cove, beads, frieze, and rais-de-coeur at the sight edge. The same moulding (albeit with slightly different proportions) frames the portrait of Madame Grand of 1783; this time surmounted by a complex and sinuous arrangement of ribbon (this is beautiful in its delicacy though most vulnerable: Cynthia Moyer stated that the carved ribbon had required strengthening and many small repairs.) Gene Karraker notes in his book, Looking at European Frames, that the oval format became popular during this time (especially for female sitters) because they were more economical to produce, requiring less carved ornamental moulding and no elaborate corners or centres.

Louise Vigée Le Brun, The artist’s brother, Louis-Jean-Baptiste-Etienne Vigée, post-1773, Saint Louis Art Museum

The middle portrait of the three, of Vigée Le Brun’s brother Etienne, 1773, is in a Louis XV-Louis XVI transitional design with swept rails and centre-&-corner ornament. The frame embodies ‘symmetrical Rococo’, where the graceful carving is rendered in carefully balanced forms – a departure from the asymmetric rocailles of earlier Louis XV frames, and a sign of the emerging taste for NeoClassicism.

Louise Vigée Le Brun, Etienne Vigée, corner detail

Cynthia called my attention to a small flourish of delicate, flat leaves on the frame; such a specific ornament might indicate a particular maker or atelier [see appendix below]. A similar motif is found on the frame for The Princess von und zu Liechtenstein as Iris, 1793, although the frame of Etienne has a rectangular sight, and that of the princess has an oval sight with spandrels; there are other differences in the various ornaments employed.

Louise Vigée Le Brun, Jacques Francois Le Sèvre, c.1774, Private collection; corner detail of frame

The portrait of J-F Le Sèvre, Vigée Le Brun’s stepfather, is in a popular Louis XVI design with an egg-&-dart motif beneath the top edge and a festoon of flowers emerging from a ribbon-bedecked central cartouche. This particular arrangement, with a central top element and swags down each side, is especially well represented in many variations throughout the show. Indeed, at least twenty of the seventy-nine paintings on view have these frames. The festoons or garlands (referred to dismissively as ‘cordes à puits’, or well ropes, by Charles-Nicolas Cochin) vary in their component parts: many are composed of husks (Princess Anna Alexandrovna Golitsyna, c. 1797, The Baltimore Museum of Art), some bay leaf-&-berry (Comtesse de la Châtre, 1789, Metropolitan Museum of Art) and others are lush combinations of many different flowers (Marie Antoinette With a Rose, 1783, collection of Linda and Stewart Resnick). There is an unusual example on Madame Etienne Vigée, 1785, private collection: rather than a rectangular or oval frame topped by a fronton or ribbons, the top rail arches up at the centre and becomes part of the large central rocaille ornament from which the festoons radiate.

Louise Vigée Le Brun, Madame Dugazon in the rôle of ‘Nina’, 1787, 57 1/2 × 45 1/4in. (146 × 115 cm); frame: 78 3/4 × 60 5/8 in. (200 × 154 cm); Private collection

Another remarkable variant is on Madame Dugazon in the rôle of ‘Nina’; the swags of bound bay leaf-&-berry cascade down each side and appear to penetrate the frame from the front, emerging at the sides.

Louise Vigée Le Brun, Comtesse de la Châtre, 1789, 45 x 34 1/2 in. (114.3 x 87.6 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Allan Harris on Flickr

Nearby, the frame for the Comtesse de la Châtre is a fluted hollow frame with a top edge of centred guilloche, and a ribbon-bedecked scrolling clasp at the crest, from which the bunched bay leaf-&-berry emerges. This clasp is ornamented with piastres between acanthus leaves; the bay leaf festoon is caught at the corners on illusionistic nails, as in the case of most of these fronton frames. Cynthia noted that the frame is not original to the painting and has been cut to accommodate the Comtesse; it is an appropriate and very successful choice.

Louise Vigée Le Brun, The Marquise de Pezay, & the Marquise de Rougé with her sons, Alexis & Adrien, 1787, 489/16 x 613/8 ins (123.3 x 155.9 cm); frame: 70 x 80 x 7 1/2 in. (177.8 x 203.2 x 19.1 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington. Photo: Marie Wise

Amongst other styles of frame on view is a magnificent tour-de-force of carving, on the large transitional Louis XV-Louis XVI frame for The Marquise de Pezay and the Marquise de Rougé with her two sons. Both front and back edges are swept, and the back edge has a guilloche moulding, both of which points are characteristic of transitional frames. The whole object is masterfully carved and extravagantly embellished. Garlands are swagged around the concave frieze of the frame, the garlands at the bottom defying gravity and arching upward.

Louise Vigée Le Brun, Peace bringing back Abundance, 1780, Musée du Louvre

Other transitional Louis XV-XVI frames in the exhibition include those on Peace bringing back Abundance, and Giovanni Pasiello, 1791, Château de Versailles. Both frames are of the same design: a top edge of egg-&-dart, a fluted hollow and a flat frieze, anchored by a sumptuous rocaille ornament at each corner that extends across the fluting and over the frieze in leafy tendrils [see appendix].

Louise Vigée Le Brun, Marie Antoinette & her children, 1787, Château de Versailles; corner detail of original frame with crest in situ at Versailles

NeoClassical designs are a striking counterpoint to the ebullient forms of Louis XV frames. While there are many loans from the collection of the Musée National des Chateaux de Versailles et de Trianon, there is a strict prohibition against photography of any of them. It is worth noting, however, that the large portrait of Marie Antoinette and Her Children (1787) from Versailles is exhibited in a rather modest frame. The original NeoClassical frame, quite grand and of significant size, was too large to fit within the constraints of the ceiling heights, so a temporary exhibition frame was made [see appendix below].

Louise Vigée Le Brun, Countess Anna Ivanovna Tolstaya, 1796, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

There is an especially pleasing fluted frame on Countess Anna Ivanova Tolstaya, 1796. When seen from a distance the overall restraint belies a sophisticated combination of classicizing ornament: a narrow unembellished top edge gives way to an assertive egg-&-dart embellished with leaf sprigs, a shallow fluted frieze with leaf buds in the channels, and a cabled astragal-&-triple bead at the sight edge. This may have been cut to fit the painting, as the sight edge does not conform to the arrangement of beads at the corners.

Louise Vigée Le Brun, Countess Anna Ivanova Tolstaya, corner detail

The show is a sumptuous offering of Louise Vigée Le Brun’s sensitive and sublime likenesses; that so many are displayed in historically appropriate frames of the late 18th century is a gratifying complement.

An appendix: some of Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun’s frames (oil paintings)

Louise Vigée Le Brun, Comtesse de la Châtre, 1789, 45 x 34 1/2 in. (114.3 x 87.6 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art; reframed. Photo by Allan Harris on Flickr

Unfortunately we cannot depend upon the many strikingly beautiful frames on Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun’s portraits being those in which they first entered their client collections; her continuing popularity as an artist has ensured that a particularly fine and ornamental class of frame has for a long period been considered indispensable to displaying her work (as with the Comtesse de la Châtre, above). However, as Bruno Pons points out relative to collections of art made in 18th century France, the frames would in the main have been fairly simple [1]. Likewise Blondel d’Azincourt, in his notes on arranging a collector’s cabinet, suggests only that the central works in a hanging may need an focal ornament at the crest of a frame, which implies that the supporting paintings had in general much less decorative settings:

‘Quelque fois même on fait ceintrer le haut de la bordure, ou l’on y met un ornement qui la couronne. Ce sera par exemple une guirlande qui surmonte le reste de la sculpture, ou si c’est un tableau qui représente un sujet, on y place les attributs qu’exige l’idée du peintre’ – Sometimes one may even highlight the crest of the frame by setting an ornament there which crowns it. There could, for example, be a garland carved at the top, or – if it is the frame of a subject painting – one might choose trophies which express the artist’s ideas [2].

Henri Danloux, The Baron de Besenval in his salon de compagnie, 1791, National Gallery, London

Both the drawings of the yearly Salon by Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724-80), and interiors such as Danloux’s portrait of Baron de Besenval confirm this state of affairs, so that the overpowering sense of carved riches in this exhibition of Vigée Le Brun’s work – although in many ways extremely just and attractive – may not reflect how the paintings were originally framed.

Louise Vigée Le Brun, The artist’s brother, Louis-Jean-Baptiste-Etienne Vigée, post-1773, Saint Louis Art Museum

Because of her association with the Queen, Vigée Le Brun had, like court painters of an earlier generation – Watteau, Lancret and Boucher – access to the carvers of the Bâtiments du roi, and her portraits of Marie Antoinette would certainly have been framed appropriately to the Queen’s status. This is less likely to be true of, for instance, the family portraits of her brother and errant stepfather, where very simple frames might be expected; yet the image of Etienne Vigée has ended up in what appears to be an example of the workshop of Jean Chérin, one of the more distinguished suppliers of the Menus-Plaisirs of the Royal Household.

Chérin stands out amongst his generation of carvers, as Paul Mitchell has established, being classed as a menuisier-sculpteur when he was admitted to the Académie de Saint-Luc in 1760, rather than as a simple menuisier or a menuisier-ébéniste.[3] His frames in transitional style, between the grand-luxe of Louis XV and the NeoClassicism of Louis XVI, are models of balance, hesitating between opulence and restraint. They are notable for several characteristics: the back edge is swept in S-scrolls like the top edge, and is decorated with a continuous intrelac moulding (not really visible in the image above); the corners and centres are symmetrical, but are set in delicate bands of rocailles; the sight edge is decorated with beading and rais-de-coeur; and the plain hollow frieze has the flourish of tiny leaves remarked by Suzanne Smeaton, above. These may be described as feuilles-à-tiges, after the example of the roses-à-tiges motif, and they appear (with the other characteristics noted) on other frames by Chérin.

Jean Chérin (1733/34–85); transitional-style frame, c. 1770, carved, gessoed, & gilded oak; modern mirror glass, The J. Paul Getty Museum

One example is the Chérin frame in the collection of the Getty Museum, now on a looking-glass, which was shown in the exhibition of frames, Louis Style: French frames 1610-1792, at the museum from September 2015 to January 2016 . The motifs used – for instance in the corners and at the crest – are slightly different from those on the frame of Etienne Vigée; however, the latter is very close to the signed frame in the collection of Paul Mitchell, whilst the Getty frame is itself signed, indicating the variety of detail possible in an item which was in the mainstream of a certain style.

Louise Vigeée Le Brun, The princess von und zu Liechtenstein as Iris, 1793, Private collection

The oval portrait of Princess Caroline of Liechtenstein has a very similar frame to that of Etienne Vigée, but the quality seems less fine, and the spandrels which fill the corners around the oval are not properly integrated into the overall design. The inner fillet, for example, which in the latter picture borders the hollow frieze next to the sight mouldings, is awkwardly islanded in the frame of the princess, and sprouts secondary rinceaux of small leaves at top and bottom which conflict with the original sprays (now transformed to ivy leaves). This might be a workshop design, but seems more likely to be a copy, since it is hard to believe that a carver as accomplished as either Jean Chérin himself, or his son, Jean-Marie Chérin (fl. 1770s-post 1806), could be responsible for such an ungainly design.

Louise Vigée Le Brun, The Marquise de Pezay, & the Marquise de Rougé with her sons, Alexis & Adrien, 1787, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Photo: Marie Wise

The painting of the marquises de Pezay and de Rougé has a frame much more likely to be the real McCoy: the plastic nature of the carving, the complex interrelationship of rhythmic arcs around the contour, the variation of form in the corners and centres, and the triumphant flourish of the enlarged cartouche at the top, all indicating a better designer and carver than the craftsman of the last frame. This work was shown in the Paris Salon of 1787, and (presuming that this indeed is original, as the inscription may perhaps confirm) the solidity and undulating rhythm of the frame must easily have created a necessary space around the painting on the vast crush of the Salon walls. Unfortunately, a museum backing frame was added to this work some time ago, so it is not possible to check for a framemaker’s stamp, and none has been recorded for it. There are, of course, other candidates for its creation; see ‘Identifying the framemakers of 18th century Paris‘ by Edgar Harden.

Louise Vigée Le Brun, The artist’s brother, Louis-Jean-Baptiste-Etienne Vigée, post-1773, Saint Louis Art Museum, corner detail (top); Peace bringing back Abundance, 1780, Musée du Louvre; corner detail (bottom)

The frame of Peace bringing back Abundance in the Louvre is an example of the straight-sided version which developed from the transitional swept frame, as NeoClassicism took a firmer grip on the collective imagination. Otherwise, the corners display many of the elements seen in the frame of Etienne Vigée – the leaf terminal, rocailles, the little leafy rinceaux, and the double ornament at the sight edge – yet nothing is as crisply carved, or as confidently composed. The undercut scrolling leaves which spring from flowers at each side of the corner conflict with the fluted hollow, and the flat frieze beyond is too narrow comfortably to contain the rinceaux, which lose all their delicacy and élan.

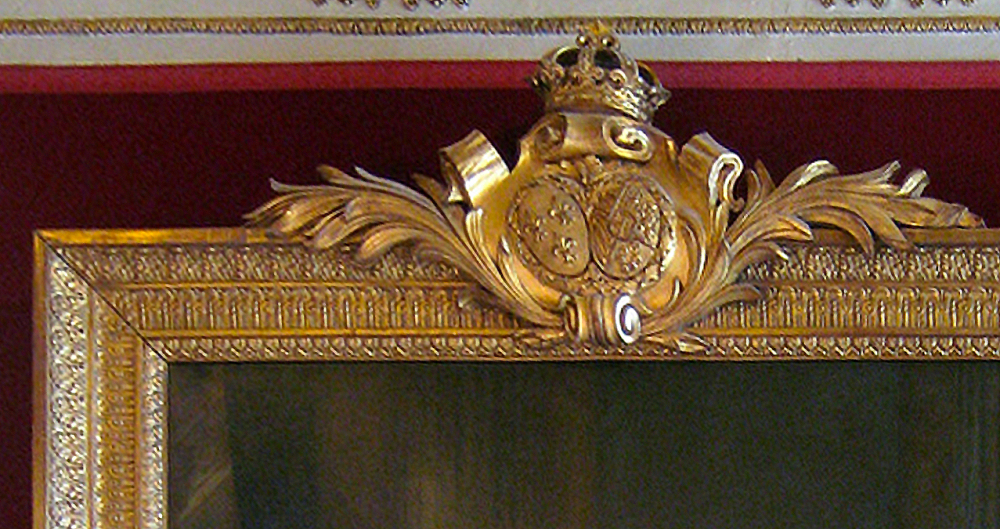

Louise Vigée Le Brun, Marie Antoinette & her children, 1787, Château de Versailles; corner detail of original frame with crest in situ

The great fronton frame on the portrait of Marie Antoinette and her children, which was too large to travel with the painting from Versailles, has moved on into the purer NeoClassicism of the Louis XVI style.

Jacques-Louis David, Mme de Verninac, 1798-99, Musée du Louvre. RF1942

It is very close to a design which can be seen more clearly on David’s Portrait of Mme Verninac – a further enrichment of the fluted concave NeoClassical moulding now framing the portrait of the Comtesse de la Châtre. The scotia or hollow fills most of the width of the rail, and is decorated with an intricate ribbon guilloche, the interstices of which are ornamented with leaves and flower buds. The ogee moulding above this is finely carved with cross-cut acanthus, and the sight edge with rais-de-coeur. The enlarged version of the pattern seen on Vigée Le Brun’s group portrait of Marie Antoinette and her children has a slightly richer sight edge, but is otherwise only aggrandized by the massive scrolled cartouche with the arms of France at the crest, supported by branches of palms and finished with a coronet. It is almost certainly the work of one of the major framemakers or sculpteurs from the Bâtiments du roi; it surrounds the portrait with a continual shimmer of light, as reflections ebb and flow across the fields of ornament – an echo of the animation the painter has bestowed on a family group which is both domestic and ceremonial.

[1] Bruno Pons, ‘Les cadres français du XVIIIe siècle et leurs ornements’, Revue de l’Art, no 76, 1987, p.41

[2] B.A. Blondel d’Azincourt, ‘La Première Idée de la curiosité, où l’on trouve l’arrangement, la composition d’un cabinet, les noms des meilleurs peintres flamands et leur genre de travail’, Institut d’Art et d’Archéologie, Université de Paris, IV, MS 34, fol.1-12, published as the Appendix to Colin Bailey, ‘Conventions of the 18th century cabinet de tableaux: Blondel d’Azincourt’s La Première Idée de la curiosité”, The Art Bulletin, vol.69, no 3, Sept., 1987, p.446

[3] Paul Mitchell, ‘A signed frame by Jean Chérin’, The International Journal of Museum Management & Curatorship, 1985, no 4, p147. A menuisier-sculpteur was the equivalent of a sculptor in wood, as opposed to the other gradations of framemaker, the menuisier or carpenter-carver, and the menuisier-ébéniste or cabinetmaker.